Note: This is an on-the-road blog post. To find out more about why I am on this trip, please read, Next book: From Kerala to Shaolin.

————————————————

A continuation of Letter from India: Kalarippayattu

The best part about being on a long research trip is that I get to meet so many fascinating people. Every day. All the time. It is actually both a blessing and a curse, because I spend hours agonising over which people to spend more time with, which ones I may develop into character profiles for the book, which ones must be interviewed right there and then, which ones can wait till a later trip/phone call, etc.

As I went through the first editing process for Floating on a Malayan Breeze in late 2010, I had to omit, with great sadness, many different characters about whom I had already written. There was “Penang Lyn”, who ran Sweet Manna Matchmaking, helping, among others, Singaporean Chinese guys looking for Penang Chinese girls, in demand because they are apparently less materialistic than KL and Singapore girls.

There was “Cherating Puru”, who let Sumana and I stay in one of his half-finished backpacker huts by the stormy beach, and then plied us with one-liners, booze and drunken management theory. There was Peter Gomes, the “Regedor” of the Malacca Portuguese Settlement, who when asked if any of the Malaysian Portuguese harboured dreams of one day returning to the motherland, replied, “Who wants to go back to a poor country?”

Now, although I have been on the road in India only four weeks, I have already met many unforgettable characters. In fact, just in the space of three days last week in Pondicherry (Pondy): everybody from Veerapan, an incredibly fit ninety-five year old master of Silambam, the Tamil martial art, to a chatty, brilliant nine-year old girl, Sama Asia, who I will probably have to include in the photo credits of this book after she adroitly handled Kirit Kiran’s Canon 40D, bigger than her head, in Auroville, her hometown.

And so as these character profiles pile up like Facebook Happy Birthdays, individually meaningful but impossible to get through, I thought I might introduce you to two of them, in the order I met them. If for some reason they do not appear later in the book, I feel happy that I have written about them here, however briefly.

Allan Waung, Cheruthuruthy

Meeting Allan Waung is a complete accident. When we are about to leave Babu Uncle’s house in Trivandrum (see first letter), I start to look for a hotel in Trichur by doing the really smart thing: consulting a ten-year old guidebook that I had borrowed from the library. Under the Trichur “Sleep” section, the guidebook says that the Cheruthuruthy River Retreat is just half a kilometre from the railway station. It fails to mention that this is the next railway station after downtown Trichur—twenty-eight kilometres away. Thus, having paid for the place online, we end up staying at a hotel twenty-eight kilometres away from our original destination—a distance that, on a good Kerala monsoon day, can take an hour.

But on a separate page of the guidebook a silver lining emerges. The Kerala Kalamandalam, an arts and cultural university, and the state’s premier performing arts centre, is in Cheruthuruthy. That works well because we are in Trichur partly to find out about kathakali, a dance, and other art forms that might have been influenced by kalarippayattu, Kerala’s martial arts (see second letter). We will go on to spend a fair bit of time at the Kalamandalam, entertained and informed by V. Kaladharan, the “publicity & research officer & S.S. in charge”.

The Cheruthuruthy River Retreat is another pleasant surprise, not only because it is surrounded by padi fields nearby and towering, blooming jungle trees in the distance; or that ten, fifteen, maybe twenty species of birds, from crows to eagles, kingfishers to pelicans, call the area home now, providing a soothing symphony as I write; or that it is here we first experience the sheer power of the Indian monsoon, a torrent of raindrops attacking the zinc roof, sounding like Metallica at its craziest; or that here we get our first Ayurvedic massage and serving of pottu, steamed rice flour and coconut, along with kadala (peanut) curry.

The Cheruthuruthy River Retreat is wonderful for all those things, but more so because as its restaurant manager it employs a certain Allan Waung.

My first encounter with Allan is when he takes my order for tea at breakfast. “Milk but no sugar, fine.” I can’t quite place him. Is he from the Northeast or Nepal? He speaks with that peculiar English accent, very proper enunciation, neither Indian nor British but somewhere in between. It reminds me in some odd way of English-educated Nepali Gurkha Officers I’ve met, or even some old Hainanese chefs in Malaya once under the employ of the British.

“Are you from Nepal?”

“Haha, why, do I look like that?”

“I think so.”

“My father came from China. I was born in Chennai.”

“Your mother?”

“She is Tamil.”

“Oh…we are on a seven-month trip from South India to North China.”

“Do you need a butler?” Allan asks, without missing a beat. “I would love to go to China.”

Sometime in the 1920s, Allan’s dad and his best friend boarded a ship in Shandong bound for Calcutta, where they intended to sell silk. That plan failed, so they set sail again, silk in tow, to another distant place, Madras. There, they eventually found their calling, as Chinese chefs. Husbands who cook are a rare commodity in India, so it is no surprise they also found love; both married Tamil women.

Allan Waung was born in 1948, a year too late as it turned out. As a little Chindian boy growing up in newly-independent India in the 1950s, he might have been aware of Jawaharlal Nehru’s blossoming relationship with Chou En-Lai. For 14 years Madras proved an open, joyous, welcoming home.

And then the Sino-Indian war of 1962 changed everything. Suddenly, according to Allan, India decided that first-generation Chinese migrants and those born in India after independence (1947) should be regarded as potential enemies of the state. They were placed under quasi-Emergency controls.

Allan essentially became a paperless, persona non grata. He could not leave Madras’ city limits for more than twenty-four hours. In order to leave Madras on a trip—even to neighbouring Kerala—he had to first visit “the foreign office” and inform them of all trip details, including where and with whom he was going, how long he planned to stay, and who he was visiting. Upon arrival in Kerala, he had to check-in to the foreign office there and provide them with the same details. On his way back, he would have to do the same in reverse.

Allan’s father, who by then was based in Delhi, where he led the expansion of their restaurant business, was also subjected to these onerous, bizarre restrictions, even when returning home to Madras. “Who is your family? How many of them are there? Why are you going to see them?” Allan blurts out, with a tinge of irritation, as he mimics the questions the Indian authorities felt necessary to ask his dad, who by that point had almost no connection to China.

For all of India’s post-independence attempts at inclusiveness, it is interesting to encounter specific ethnic or socio-economic groups who have been disenfranchised. I’ve read about other ethnic migrant groups villified during international warfare, such as the Japanese Americans interned during the Second World War, but this is the first time I’ve heard about the persecution of the Chinese Indians. It’s a topic, given the scope of my book project, that I’ll be looking closely at.

In 1965 Allan was given “foreigner status”. Having an interest in engineering, he joined Ashok Leyland, an Indian manufacturing conglomerate, and worked with them for eight years. In 1973, Ashok Leyland wanted to confirm him as a full-time engineer in the firm. However, because Allan had still not obtained Indian citizenship—eleven years after the war, twenty-five years after he was born in Madras—the company terminated his services.

Thus, despite Allan’s engineering education, upward social mobility for the Waung family would have to wait one more generation. With few other options available, Allan became a chef like his dad. Then in 1976, he finally got his Indian citizenship, and got married to another Chindian—the daughter of his dad’s best friend.

Allan’s cooking career took him to many places, including Doha, and Singapore in the 1990s, where he worked for several different companies. “Those days, very easy to change jobs in Singapore,” he says. “I was there when they banned chewing gum.”

Today, Allan is one of the most polished, attentive restaurant managers I’ve ever met. His slightly-greying hair is always neatly combed, his tie perfectly centred, and his eyes ever alert—if you can see them: they are hidden behind rectangle spectacle glass that seems to reflect any available light source.

Allan pairs methodical observation skills with an unerring memory. He remembers the way I take my tea, the name of my wife, who he meets via Skype, and the fact that I never finish all my rice or roti—a legacy of me residing in the US when the Atkins craze was sweeping the country. He can also surprise, like when he brings me a plate of jackfruit in the middle of the afternoon, because “I know you like durian”; or when he proudly shows off his Singlish, “Oh, you haven’t come for ‘ma-kan’!” when I ask only for tea at half-past six in the evening. It almost seems like Allan Waung’s considerable skills are wasted on this remote resort on the outskirts of Trichur.

There are so many other fascinating, peculiar, characteristics of Allan Waung, including the tragicomedy of how he developed diabetes. In the 1970s, while working for the Chola group in Madras, he was the official “sweet taster”. Every morning, he would have to sample Indian mithai—saturated with ghee and sugar—before they left the factory. “On some days, during holiday season, we would have to taste shipments of one to two hundred kilograms,” he says. I am not sure whether to laugh or cry, thinking about poor Allan Waung, denied by error the right last name (“It’s actually Wang”), denied citizenship, denied a career as an engineer, and then forced to taste ladoos every morning for five years.

Finally, as you, dear reader, will be following me on this journey, it is important that you know what Allan Waung gave me before Kirit and I left the Cheruthuruthy River Retreat.

Allan admits that he feels little connection to either China (“I’ve never been there”) or India (“They made me wait eleven years before accepting me”). Nevertheless, Allan has been carrying on a snail mail correspondence with a cousin and uncle in Shandong, as if grasping on to the only remnants of a long-lost ancestry. The last letter he sent was in August last year; they have yet to reply. “Long time. Perhaps my dad’s cousin has expired.”

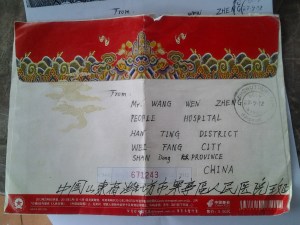

He gives me a photocopy of the last envelope they sent (pictured), and says, “Maybe you can visit my relatives in Shandong.” Among other things, Allan wants me to photograph his father’s land.

(pictured), and says, “Maybe you can visit my relatives in Shandong.” Among other things, Allan wants me to photograph his father’s land.

“My father was the only son.”

“Well, knowing China, somebody’s grabbed the land by now.”

“But I don’t want it,” Allan concedes. “I just want to see it. My roots.”

Exciting! A little hunt that connects the two countries. I promise I’ll try my best to find his relatives, and promise to bring Allan some lap cheong, Chinese sausage, the next time I visit.

“It’s so good. You can just eat it alone with plain rice,” he says. “But it’s very hard to get here in India.”

Hop on Gurls, Bangalore

If not for the traffic, I think I could live in Bangalore. The weather is cool, like having on a constant light air-con, even if smog and general global warming mean one no longer has to “wear a sweater every evening”, like Babu Uncle did when he was studying here in the 1960s. The food is yummy, be it three rupee chilli pakoras on a dirty back street near our hotel in the bustling Gandhi Nagar area, or three hundred rupee Sicilian pizzas, whose freshness and thinness impress, and which I wash down with a glass of Shiraz in the swanky UB City mall, both courtesy of Rahul Mathew, Babu Uncle’s son, who seems intent on outdoing his dad’s hospitality. Then there is the vibrant live music scene, even on a Sunday covers night at Take 5, a “gig pad” in Kirit’s words, where Pushing Tin delight with their range, including The Doors’ Love Me Two Times and A-Ha’s Take on Me; the evening reminds me of Singapore, and long Jack & Rai sessions at Walas.

But I am most intrigued by the mix of people and social dynamics here. Bangalore is a melting pot. There are people here from all over India; many have come to study or to work, often in the IT sector. Caste, race and religion seem to matter less. And, most importantly, for the first time in a month travelling in India, I feel like the women are on a somewhat equal footing with the men.

Keralites, proud of their matriarchal traditions, may bristle at the suggestion. But in Kerala, although women are educated, respected and often inherit the land, gender roles seem much more entrenched.

In the admittedly brief five days I spend in Bangalore, well, things just seem a little different. The first morning we are there, I am surprised when the tiny female hotel receptionist barks at the male restaurant manager after he mistakenly charges me for a complimentary breakfast. Women seem a lot more daring in their dress, men less in their stare. When two young men on a motorcycle ride past a single girl walking on the road, they seem less prone to honk and turn and ogle and wink, something I had noticed frequently in Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Finally, one can tell a lot about gender differences by how open a society is to intoxicants. In most of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, the only place I see women having a drink is at home. Almost every bar I visit—liberal Pondy aside—is exclusively male, if not by design, certainly by custom. Women only very occasionally have the odd drink at a family restaurant.

In Bangalore, Kirit takes me to Peecos, one of his favourite bars, which is ensconced in yesteryear, from its Jimmy Page quotes on the menu to its impressive collection of dusty cassette tapes that the DJ cycles through, perhaps rebelling against the technology that, for better or worse, has swamped the rest of the city. It is barely three on a weekday afternoon, yet Peecos’ top floor is full of students, including many girls, guzzling pitchers of beer, smoking cigarettes, laughing loudly and having a ball of a time. Kirit and I gleefully join in the revelry.

Puritans might frown at this supposed decadence, but in it I see mostly signs of gender equality—men and women doing here what only men do in many parts of India.

Given all that, I am terribly excited when Kirit tells me he’s arranged for us to meet with Hop on Gurls, a group of Bangalorean biker girls. Before meeting them, I assume that this is a group of women that comes together to offer mutual support and inspire confidence when riding small motorcycles in a clogged, congested city.

Shock #1: They are actually learning to ride a 350cc Royal Enfield Thunderbird (pictured, known simply as a “bullet”). The bike is so big that some of the smaller girls, like Divya Chandrasekharan, a Mallu who grew up in Bangalore, have to tip-toe when balancing the bike at a stop. “Like ballerinas,” she says.

Shock #2: They are learning not only to ride in Bangalore and surrounds, but most harbour hopes of faraway adventures, including “Lei-Ladakh”, the holy grail of long-distance riding for them. Indeed, many are keen to ride their bikes from Bangalore all the way to the Himalayan foothills, more than three thousand kilometres away. (The alternative is to fly there and rent a bike locally; or transport bikes in a train.)

Shock #3: They are learning not only the joys of riding, but the mechanics of the engine. One of their lessons involved a stripping down and reassembling of the engine’s parts.

Many enthusiast drivers/riders in Singapore are wary of even crossing into Malaysia, right next door, and probably have never before changed their own engine oil, let alone strip an engine, so I am suitably impressed by this point.

Hop on Gurls was conceived by Bindu Reddy and Lionel Lobo, who I meet, and two other friends, Raghunadan and Mrudul.

“Did you start it because you wanted to help girls who had nowhere else to learn?” I ask Lio.

“No, I started it because Bindu kept bothering us [to teach her],” he jokes.

Bindu is the undeniable gang leader, as it were. With her long jet black hair, maroon lipstick, tight jeans and aviator sunglasses, she certainly looks the part. Originally from Bangalore, she now lives in Bombay, where she is completing her MBA. The group’s activities seem to ebb and flow with her presence, partly because of her energy, but also because she holds the keys to the red bullet that the group uses, a bike that because of numerous minor knocks and falls looks much older than its five years. Kirit and I are lucky that our trip coincides with her holidays back in Bangalore, when she organises the weekend training sessions. “LEARN the BULL RIDE your WAY”, as one Facebook event is called.

A video of Hop on Gurls (HOGs), courtesy of Lio Lobo

The training regimen involves Bindu or one of the other instructors—Divya, Swathi Reddy, Vinutha Pg—riding pillion behind the trainee on a short twenty to thirty minute course around a quiet, posh part of Koramangala, a Bangalorean suburb. They are gentle, but firm on occasion. “Oi. Where is your foot?” Divya, affectionately known as “Mother India” or simply “Mummy”, snaps at one of the trainees. They spend six to seven hours there, taking turns riding, and chatting incessantly in between.

For as much as Hop on Gurls is about big bikes and adventure, it is about friendship. Most of the girls didn’t know each other before signing up. “It is an opportunity to meet people outside the usual work and college circles,” Divya says. Facebook is their main communication portal, and their Group now has more than 900 “Likes”. They once had a member based in Chennai, who would travel the three hundred and fifty kilometres to Bangalore for the weekend, just to ride. And another one from Mysore, who would wake up at 5am, take a five-hour train to Bangalore, join them for a day of riding, and then take a five-hour train back home. “Even when we are tired, knowing there are people like that motivates us,” Bindu admits.

Through the Facebook group Bindu has even managed to meet somebody in Europe who will lend her a bike this summer during her trip to Italy. It is impossible to individually describe all the great Hop on Gurls here—indeed, given how fiercely independent they each are, I worry slightly about discussing them collectively in this piece, as if a group of girls is the equivalent of one elderly Chindian Allan Waung. But I imagine they will just give me a hard time the next time we meet, the same way they do when I eat only one parotha at lunch at the dhaba, while two of them share three. “You are a growing boy, you should eat,” they tell me. (The oldest of them is seven year my junior.)

But what about traditional gender roles and expectations? “Our fathers are grudgingly proud of us,” Divya says, “and our mothers gave up on us a long time ago, haha.” Moreover, contrary to what I had assumed, it seems like most guys on the street are not too bothered when a young girl pulls up beside them in a much bigger bike. “Even if they said something, we wouldn’t know, cos we’re too focussed on the road,” says Divya.

So, as Kirit and I ask our questions, trying to puncture stereotypes about women’s roles and concoct cliches around female empowerment, it soon dawns on us that this group of girls is far less gender-conscious than we are.

Nevertheless, let not my dreamy musings about liberal Bangalore paint too rosy a picture. Just like in developed countries, from Singapore to the US, I am certain every lady here has experienced discrimination. Divya and another small-sized biker girl find shared solace when recounting boardroom tales of being looked down on. “Are you an intern?” is how many older male executives choose to greet them.

Meanwhile, the official reason bars in Bangalore shut at 1130pm is to reduce late night crime. “I wouldn’t feel comfortable if my mum or girlfriend was out alone at night,” admits Rahul, my cousin.

Separately, not everybody agrees that Bangalorean food is the bomb. Benjamin Tan, a Singaporean architect who has only just moved to Bangalore to start work with CPG Corporation, a Singaporean firm, laments that there is masala in everything. I remember the Masala Pepsi that I try for the first time with Divya and two other friends, Niyothi (Lio’s wife) and Sneha.

Many Malayans I know, when abroad and missing home cooking, consider instant noodles the ultimate, ubiquitous comfort food. Not here. “Even all the instant noodles are masala flavoured,” Ben, who is otherwise loving Bangalore, grumbles.

Somehow that thought doesn’t bother me much. Perhaps it is not so much Bangalore that I can live in, but India that I am getting used to.

The story continues at Letter from India: Philosophies.

Allan Waung, Cheruthuruthy

Hop on Gurls (plus one wannabe Gurl and Lio Lobo), Bangalore

(For more photographs, please see Photos from India: People)

Post-script

How much/what should an artist give back?

This is something that all artists, particularly writers and filmmakers, grapple with. It is all fine and dandy parachuting in to some remote community to record their lives, but what debt or obligation to them does the (arguably voyeuristic) artist have?

It is a question that came up during a Q&A session at the 6th International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala in Trivandrum. At the very least, said one filmmaker, she sees the need to show the “subjects” the film and seek their feedback, if not necessarily their approval.

As I was writing Floating on a Malayan Breeze, I told myself that if it ever got published, Sumana and I would retrace our path around Malaysia–by car, bicycle tak boleh–to visit the people we met and wrote about, and give them copies of the book. We have yet to do this. This bugs me.

After meeting Allan Waung, all sorts of ideas about “giving back” flood my mind. Yes, perhaps I can help him track down his relatives. Perhaps I can organise a Skype call for them. Better still, if the book or related activities can generate enough money, perhaps I can even fund a trip for Allan Waung to visit the home of his forefathers, fulfilling a lifelong ambition.

Getting ahead of myself? Perhaps.

The downs…

So far I’ve mostly shared with you the uplifting, cheery stories. Of course, there have been a few downers too. Here are two.

Hotel nightmares: I have a daily accommodation budget in S$. With the rupee’s sharp decline, Kirit and I have actually managed to stay in fairly comfortable (i.e. 3-star) hotels. The one place where we couldn’t find anything similar was in Kasaragod, in the northernmost part of Kerala. There are few hotels there. So we opt for a Rs.900 (S$20) place.

The cold shower and dirty bedsheets don’t bother me that much. What really gets me is the damp towels, which I have to dry under a weak fan before using. The first night, perhaps because of the whisky on my breath, I don’t notice anything too sickly. But the next morning, as I wipe my face, I almost faint under the smell of the last three hotel guests.

Note to self: pack own towel, and don’t drink so much whisky.

Selfish journos: It’s actually been a while since I met a selfish journalist that reminds me of classmates in primary school who would never let me copy their homework. But in Bangalore I do. When I go to visit Krishna Prathap, a kalarippayattu master in Bangalore, there is another journalist there to interview him, on the eve of the national kalarippayattu championships in Trivandrum.

I am there first and am chatting with Krishna. Sensing that his students are calling, I tell Krishna I can wait for the next break. This other journalist nips in, steals Krishna away, and starts firing off a series of basic background questions. Overhearing this, I walk towards them, introduce myself as a writer from Singapore, and ask politely if I can listen in–so that Krishna and I can save time, and not have to go through the same stuff all over again later.

“I’m sorry, but this is an exclusive interview for the XXXXX paper” this person dismisses me with a pout, and tells me to leave.

I feel like telling this person that he/she is not Christiane Amanpour and that Krishna Prathap, for all his strengths, is not Bruce Lee. But I suck it up. Kirit tells me that this is how many young journos in India behave, to ward off the many lazy leeches around.

Oh well. I remind myself there will always be people like this around.

Hi Sudhir,

I meant this as a comment to your last post, but because your next one has arrived and read, allow me to post here.

Having returned to India after 15 years in Singapore I can fully sympathise with the frustration you are currently experiencing in India. I am working hard at weaning myself of the ‘incurable addiction’ to conveniences that we take for granted in Singapore. But I am happy that you are putting them behind, to concentrate on your work and to appreciate what India has to offer.

I am based now in Bangalore, too bad we didn’t connect when you passed through, but let me know if you come again. Allan Waung’s story was poignant and beautifully written. I have mostly encountered only three types of immigrants: those who move to another land and leave their homeland behind without angst. These are the immigrants who have made peace with their new homeland. The second type never really leave home. They go abroad for work or study and then return home right away. The third type are happy in their new country but can never really leave their homeland behind. They are torn between two cultures. I belonged in the third group. But in a totally different class and well told, stories like Allan’s are stuff that one usually encounters in great literary fiction/biography and it was gratifying to read it in a blog post.

Venkat

Thanks Venkat, appreciate the feedback!

Love your writing! 🙂

pls contact allans wife shirley waung. he is no more.